The quest to decipher how the body’s cells sense touch

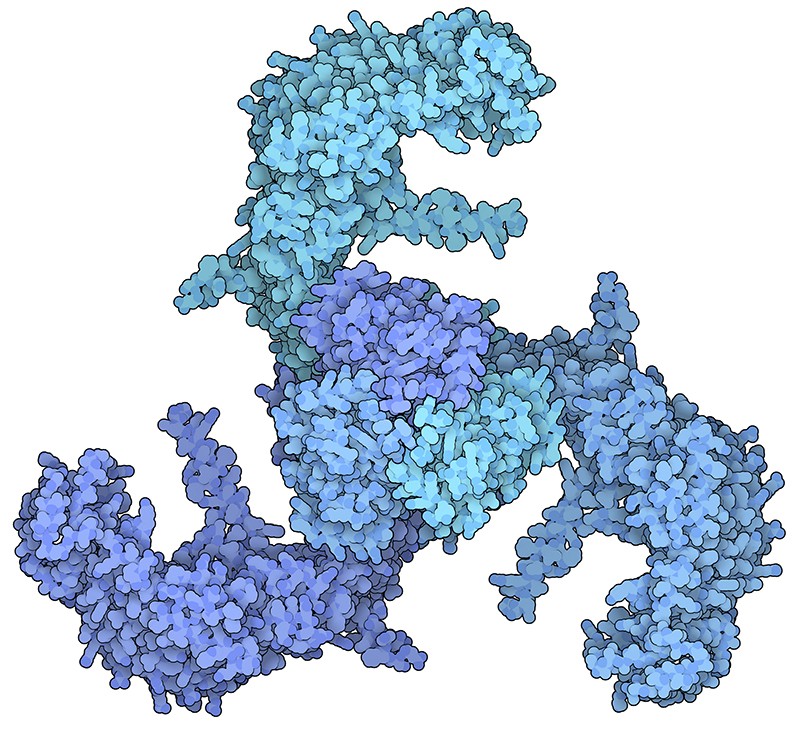

The discovery of Piezo2 and a related protein, Piezo1, was a high point in a decades-long search for the mechanisms that control the sense of touch. The Piezos are ion channels — gates in the cell membrane that allow ions to pass through — that are sensitive to tension. “We’ve learned a lot about how cells communicate, and it’s almost always been about chemical signalling,” says Ardem Patapoutian, a molecular neurobiologist at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, whose group identified the Piezos. “What we’re realizing now is that mechanical sensation, this physical force, is also a signalling mechanism, and very little is known about it.”

Patapoutian’s team, meanwhile, is looking for entirely new channel families. In 2018, he, Murthy and Scripps structural biologist Andrew Ward reported what they think could be the largest group of mechanically activated channels. They knew of a protein family that helps plants to sense osmotic pressure — the OSCA proteins — and reasoned that they might sense force more generally. In human kidney cells, OSCAs did indeed respond to Murthy’s stretching of the cell membrane14.

The channels discovered so far cannot explain all instances of cellular mechano-sensitivity, says Murthy, now a biophysicist and neuroscientist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. More mechanosensors must be out there. And those sensors probably have more jobs than are known today, says Patapoutian. “We’ve just barely scraped the surface.”

Comments

Post a Comment